Dorset Buttons

By Adeline Panamaroff

Adeline, a freelance writer/proofreader, located in Edmonton, Alberta can be contacted at www.adelinepanamaroff.com for writing and marketing requests.

History: The clear origins of Dorset buttons remain somewhat shrouded in the mysteries of the past. For instance, we do know for a fact that Abraham Case, while serving as a soldier in France during the 30 years War, either got inspired by seeing French soldiers make replacement buttons on their uniforms utilizing a twist of cloth over a form and then stitching the cloth taut before attaching it to the garment. Alternatively, he may have seen the lace buttons made in Brussels and used them as a basis for what he would further develop when he settled in the Dorset area of England.

Dorset in the 1600s had mainly agricultural and sheep-based industries. Case wanted something more ambitious to pursue in order to support himself and his new wife, whom he married in 1622 C.E.. Up to this point the use of buttons in everyday English clothing is not especially common. While the use of buttons was widespread on mainland Europe and beyond, England lagged behind and most garments were still fastened with laces or pins. Abraham Case and his wife set up shop together, manufacturing thread-covered buttons that used sheep horn as an underlying base. The Dorset area, having a large sheep industry, was a good source for this foundation material. These early Dorset buttons had two grades. The top quality grade were called High Tops which used the very tip of the horn as the form which was then covered with a small piece of linen that was covered with a web of thread stitching. These buttons were sought after by the nobility and aristocrats. The second grade of button, called Dorset Knobs, used a disc of horn that was also covered with a piece of linen and then stitched over with a thread design.

During the early decades of Case’s button manufacturing, the fashions of mainland Europe finally came to the shores of England and the use of buttons to fasten garments became commonplace. The demand for the locally manufactured Dorset buttons took off and Abraham had to expand his workforce in order to keep up with the demand. He took up the services of local rural women throughout Dorset and surrounding areas in order to produce buttons, en masse.

Dorset button manufacturing remained a family business for many generations. The first major innovation was introduced by Abraham's grandson Peter Case. By this time the use of sheep horn was becoming a problem as the supply was dwindling. In response to this Peter developed a special rust resistant metal alloy that he could form into wire. This wire in turn could be formed into rings which, when dipped into solder, created a seamless form onto which a network of threads could be woven or stitched to fill in the ring and create what is now known as classic Dorset buttons.

Both the manufacturing of the rings, the soldering process, and the final manufacturing of the finished buttons employed thousands of individuals in the Dorset area in the late 1600s and the majority of the 1700s. Demand for buttons was so high that being involved in this industry as a buttoner was far more lucrative than any agricultural activity. The original material for buttons on mainland Europe, bone, ivory, or other naturally occurring materials, were extremely difficult to come by for the average commoner. When Abraham Chase introduced his local style of button and when the fashions of fastening garments with them emerged in Britain, the demand for Dorset buttons exploded. Not just rural women but also children and often orphans were employed in the making of the rings, called twisters, and dippers, individuals who dipped the rings into solder.

To organize the business more effectively, depots were set up throughout the Dorset area where individuals could both drop off their finished button products in exchange for their fees as well as where they could pick up materials, such as the rings, to create new buttons.

There were several grades of button quality. For ease of transport as well as for sorting different grades of quality, Dorset buttons were mounted on coloured cards. Pink coloured cards denoted the highest quality of button and were reserved mainly for the nobility. Buttons mounted on black coloured cards represented the second grade of quality and were mainly utilized by the middle class. Buttons mounted on yellow cards were of the lowest quality and were destined for use on work garments. The sorting and sewing of the buttons onto the cards was again often the work of children and those who are housed in orphanages.

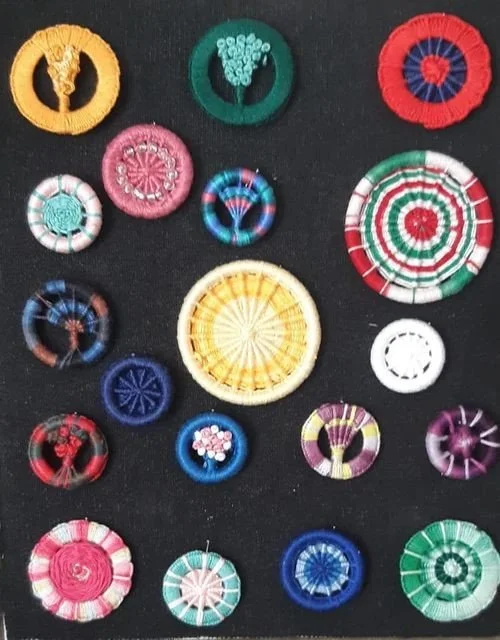

Many different styles of Dorset button emerged in the centuries of their manufacture such as Blandford Cartwheel, Basket Weaves, Ten-Spoke Yarrels, Grindles, Honeycombs, Bird’s Eyes, Mites, Cross-wheels and Singleton. Different colours of thread could be used, or if a specific colour was desired, buttons could be boiled to remove the existing colour and then re-dyed to produce a specific shade of button. The demand for this style of button grew to such a size that they started to be exported for international trade.

This extremely successful cottage industry came to a screeching halt when Benjamin Ainsworth patented and showcased his mechanized button making machine at the Great Exhibition in 1851 C.E. This machine could manufacture cloth-covered metal shank buttons at a rate that far exceeded the capacity of handmade Dorset buttons. With the advent of this industrialized method of creating buttons in a much cheaper fashion, the Dorset button industry collapsed within itself. This left thousands unemployed and destitute. Some buttoners were able to transition into other industries such as needlework and the manufacturing of gloves. The vast majority however were forced to migrate to areas such as Australia, Canada and the United States in order to start over with new ventures abroad.

In the early 1900s Dowager Lady Lees tried to revive the manufacture of Dorset buttons. She traveled around the Dorset area to study and document the different styles of this button and then went on to create a small business in Lytchett Minster. This business created buttons in the colours of the different political districts in the Dorset area as a way for the politicians in the area to campaign during times of election. These came to be called Parliamentary Dorset buttons. Unfortunately, World War I crushed this business venture as the focus of financial resources turned to matters of defence.

Today Dorset buttons and their manufacture is something that is enjoyed mainly by people interested in the fiber arts. It is probably thanks to the work of the Dowager Lady Lees that many of the different styles of Dorset button were documented and passed down through the generations.

Technique: To make a Dorset button you need either a metal or plastic ring as the form. Using pearl cotton thread, blanket stitches are worked very closely around the entire ring until it is completely covered. This is called casting on. Then you slick all these stitches inwards which is turning all the bumpy ridges of the blanket stitches to the inside of the ring. Then there is the laying, which is the working of the thread across and around the ring to create a network of spoke-like threads that meet or cross at the middle of the ring. From there is the rounding which is the interweaving of thread through the spokes to fill in the inner area of the ring. The method of rounding varies depending on the style of Dorset button that is being made.

Innovation: Today most Dorset buttons are made on a plastic ring form. These make the button more lightweight for both working and for use on garments. New uses of Dorset buttons can be found in works of art such as small tapestries. New additions to old styles such as creating lacy fine crocheted edges around the outside of the button can also be seen. The incorporation of beads to the interior or to the outer ring of the button are also used to create a multimedia work of art.

References and Further Reading:

Note: The links above lead to external content. ENG is not responsible for the content of external sites.